It’s almost eerie. The first time you hear it approach, if you’re like my neighbor Ernesto, you may think it’s a bumblebee – or, to be more precise, the aggressive solitary bees called ronsapas that inhabit stumps of dead wood and defend their territory by way of nasty stings. From a jungle perspective, you’d surely be forgiven for hitting the deck or breaking into a run when the sound first reaches your ears – that characteristic buzzing hum.

It may not surprise you to learn that in our almost unbelievably technology-saturated, increasingly globalized world, even rainforest farmers know exactly what that sound is – a drone. Call it tech appeal, or the stereotypical gadget fixation of the grown-up boys of the world, but drones are just about everywhere these days, including in the Amazon of Peru.

Over the course of the last 15 months, Camino Verde has had the opportunity to put these instruments to valuable and surprisingly varied use – and save an incredible amount of work at the same time.

Consider this: Last year, our Reforestation Center team, under farm manager Olivia Revilla and with the help of several interns, set out on an ambitious mission to document the trees we’ve planted. That totals around 50 acres of trees, tens of thousands of trees, representing our reforestation efforts of the last 10 years and the tangible manifestation of our donors’ commitment to Amazon restoration.

As you can imagine, making a map that includes every single tree and keeping track of basic data for each – such as species, botanical family, height, diameter at breast height, etc. – was an incredibly time-consuming task, a labor of love aimed at helping us better measure our impact. Months of work later, we had our first map for wide swathes of the farm – though not the whole planted area.

We celebrated this first achievement and prepared ourselves mentally for the work involved in finishing the task. It was right around that time, as we were contemplating methodologies to improve our efficiency for this arduous data collection, that a small group of Wake Forest University students paid us a visit and flew a drone over the reforestation center for the first time ever. The images captured were incredible. It was frankly breathtaking to see the trees from above – to see how clearly the mixed agroforestry systems we plant resemble the wild forest.

Given the meteoric rise of drone technology, maybe it doesn’t come as a surprise to learn that in the following months, there were many more drone flyovers to come. Our friends from Pacha Soap paid us a visit in February and captured breathtaking video of one of the largest, most impressive trees in 200 acres of primary rainforest areas we protect. And then Wake Forest’s Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica (CINCIA) research group – our staunch allies in reforestation and restoration activities in Madre de Dios, Peru – returned and flew again.

To my amazement, after the last of these visits, we were presented with a map that the drone had made for us. By taking pictures of the ground at regular intervals and using software to stitch the images together, we got a better and more detailed map than from satellite or GPS. Beautifully photographic, the map showed us our trees as they appeared from above. And further, it did the work of months of hand data collection in the span of a day.

As you may know, Camino Verde values monitoring and evaluation, which means we follow up on the trees we plant so that we can say clearly and unequivocally what our impact has been. Drone technology is allowing us to greatly reduce the time and energy we spend on this necessary activity – so we can spend more time on our real work, our real passion, the planting of trees.

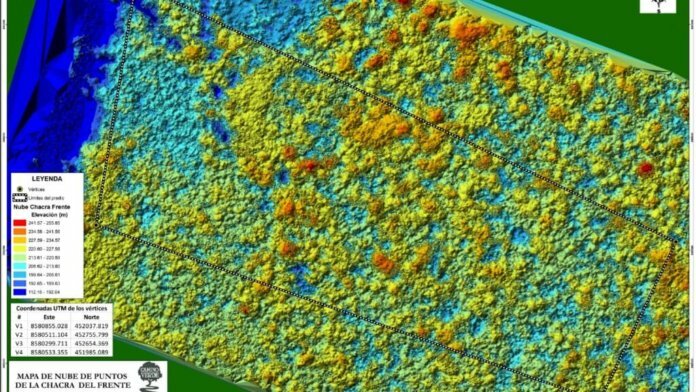

While a photographic map is valuable in and of itself, more targeted drone work has given us an additional something that seems almost impossibly futuristic: a three-dimensional diagram of the canopy of trees of our reforestation center. This 3D point plotting tells us the height of trees, the size and shape of their canopy, and – we hope, soon – the ability to calculate ever more accurately the carbon captured and stored by our trees.

In addition, annual flyovers allow us to closely monitor the protected primary forest area I mentioned earlier. By comparing maps, we can notice trees that fall in storms, from old age or by human hands.

Sure, technology is far from a panacea. Human technology is obviously responsible for enormous destruction in our world. And true solutions are found first and foremost in the hearts and minds of people, not in gadget wizardry whose origin, it must be remembered, is military in nature. But placed in its appropriate role as a tool of human ingenuity, an extension of our eyes and hands, some technologies can help us bring about restoration on a previously inconceivable scale. Drones aren’t the answer – but they are a valuable piece in a toolkit for landscape stewardship that also includes several perfectly respectable devices that date back to the Stone Age.

Robin Van Loon is the executive director of Camino Verde, which partners with Amazonian farmers and native communities to regenerate Amazon forests and improve livelihoods.